Whether we personally identify as an introvert or an extrovert, a loner or a team player, we all yearn for a connection with other people, especially the people who should love us the most: our families. But sometimes life doesn’t work out that way, and we’re left with a big, empty hole where all of that love should be.

The most perplexing thing about this is how important that love and connection are to our development when we’re small. The first years of our lives, in fact, are formative well beyond our understanding of the world around us, shapes, letters, communication, and walking. It’s also when we learn about our ability to connect with other human beings, and whether or not we can rely on them to meet our needs, connect with us, and love us. That absence of support, protection, and comfort is detrimental to a baby’s development and can impact their future perceptions of the world, themselves, and their relationships with other people.

“A Baby’s Perspective” Photo by @charlesdeluvio via Unsplash

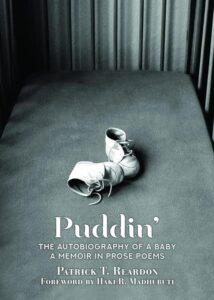

Poet and former Chicago Tribune reporter Patrick T. Reardon refers to that absence as “the blank lack” in his memoir of prose poetry, Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby: A Memoir in Prose Poems. After spending hours looking at family photos of his first year on earth, as well as early photos of him with his first sibling, David, Reardon was able to draw conclusions about his relationships with the other members of his family, which proved to be accurate after cross-referencing with those family members.

Reardon noticed in these photos that his father (referred to as he/him in Puddin’) appeared uncomfortable when holding his baby, as if someone had passed a random baby to hold for a few moments rather than holding his own child. Reardon’s mother (called she/her in the collection) appeared similarly disassociative, never holding her baby close, often pushing him to arms’ length, and usually looking away, clearly more inconvenienced at holding her child than thrilled. In his own facial expressions, Reardon noted that he frequently held a “thousand-mile stare” and did not smile when held by his parents. Raised in these conditions of poor connection, it seems a baby will learn not to expect close relationships after months of not receiving them.

Though Reardon later agreed with his brother that they did not have bad parents and that they simply were “the way they were,” Reardon still wanted to explore what his life must have been like during that first year when he was learning about the world and was as yet unable to verbally vocalize his needs. After discussing their early experiences with his siblings and further exploring the family photographs, Reardon began to write prose poems that served as memories of those early, formative months. Though they are not his literal memories, Reardon grew to view the project still as a creative memoir, fueled by facts, informal interviews, and photographs.

What comes of the former reporter’s research is a collection that anyone who has experienced abandonment, neglect, a lack of reciprocated love, or loneliness needs to read.

The concept behind Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby might be misinterpreted at first glance as simplistic or, worse, inaccurate. It is, after all, a collection of prose poetry being presented as a memoir, despite the fact that they’ve come from a baby’s presumed, not actual, memories. These are the rebuttals a reader might make before stepping into the world of these poems, however. Despite concerns about what constitutes a memoir or fact, it’s the essence of these poems that is so striking, so encapsulating, and what has been surmised from actual conversations and familial documents on these pages breathes as authentic and factual. Any concerns about the genre fall away as we take in the needs and desires of the baby we’ll never be able to pick up.

The concept behind Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby might be misinterpreted at first glance as simplistic or, worse, inaccurate. It is, after all, a collection of prose poetry being presented as a memoir, despite the fact that they’ve come from a baby’s presumed, not actual, memories. These are the rebuttals a reader might make before stepping into the world of these poems, however. Despite concerns about what constitutes a memoir or fact, it’s the essence of these poems that is so striking, so encapsulating, and what has been surmised from actual conversations and familial documents on these pages breathes as authentic and factual. Any concerns about the genre fall away as we take in the needs and desires of the baby we’ll never be able to pick up.

Because that’s the exact conundrum of this book: empathetic readers will want to reach right down through these pages and pick up this baby who’s longing for it. Despite the fact that we’re experiencing this journey through words on the page, and even though those words were written by the fully grown version of this baby, we long the fill the void in what we are reading. In this baby persona’s blank lack, we discover our own.

Throughout this collection, we are confronted by an inattentive, apathetic, and clearly inconvenienced mother, paired with an equally apathetic, not-a-father-figure dad, allusions to affairs and lust, darkness, loneliness, abandonment, moments of love and reprieve that are over much too soon, and perhaps the worst thing of all: a repeat of what we know will be the exact same cycle and dynamic… through the arrival of a second child.

It’s only through Aunt that we experience moments of loving reprieve in the collection, and her visits are few, far-between, and brief. But it’s telling that Aunt, Gram, and Paw, are the only names used in the collection until the arrival of David, the persona’s younger sibling, on the final pages. The only other name that appears is Puddin’, which is the loving nickname that Aunt has given the baby and which makes the baby smile. Puddin’, in fact, only smiles, experiences the outside world, and engages in activities without hesitation when in the presence of Aunt. Any other attempts that he makes, like rolling over or walking along the couch, are paired with hesitation and foreboding, the baby making glances over at an aloof parent who is not watching or who is ready to hide the baby back in his crib like an object that has been conveniently been placed back on its shelf at the slightest sign of noise or protest. It’s through Aunt that Puddin’ finds a beacon for love, a light of hope, and an example of what love should look and feel like.

THREE: January 10, 1950

Aunt’s eyes smile. Her voice smiles. My

eyes go wide with joy. The skin of her face

is soft on the skin of my face. I feel her and

lean all of me on her. She hugs me on her.

The weight of her arms feels good, like I

am part of her. The length of her on the

length of me feels good. I look at her eyes.

They look at me. A line runs from her eyes

through mine to deep in me. She calls me

Puddin’.

There’s a stunning duality to this collection between what is and what isn’t, what the baby wants and does not want, and contrasts between moods and sizes, that appear throughout these prose poems. Even in the very first poem, when the baby is at his youngest, he already wishes that his mother (she/her) was in the room with him but also hopes for him to be gone. There are other times when he wants to be picked up but not held or touched. There are comparisons between his interest and passions in the objects around him compared to his parents’ aloofness and bitterness. It seems like such a thing, to compare contrasting things, but when we think about the fact that this is from the perspective of a baby who is figuring things out, and we think about how complex these lessons are (like what love actually is), the dualities speak volumes.

Perhaps my favorite insertion into this collection is the concept of lines. The baby sees these lines connecting people, through eye contact, through objects, and even through his body. It’s a reminder that we are all connected and that everything we do, see, touch, taste, and experience is cyclical and shared with other people. It’s beautiful and gives off this very literal image of visceral threads that define us, make us, and entangle us.

THIRTY: June 6, 1950

In the dark, I wake. I see the shades of dark.

I hear birds. Their sounds are lines from

one to the other. Their sounds are lines

from them to me. I close my eyes. I sleep.

NINETY-ONE: December 29, 1950

I see the line that runs from Gram to Paw

and from Paw to Gram. It is a line that has

bumps and frail parts. I want a line that is

strong that I can share. I need to be a big

one for that. But I have a line to Aunt when

I see her.

In the foreword, Haki R. Madhubuti says that this has never been done before, which I think may be right. Though I can recall poems that featured babies, and perhaps even referenced back to an experience the writer may have gone through as a baby, I cannot think of other depictions written as if coming from the baby’s mouth and mind, let alone an entire collection seated in that form of consciousness. It was truly enthralling to read and to ponder. Love, for example, is such a complex thing to understand, but our want for it is so simple. That’s honestly what makes this collection so relatable, really for anyone, is our very basic, simple needs and wants for larger, more complex things that form us and shape us.

Madhubuti also says that what Reardon has done may never be done again, which I honestly hope is not true. Though it’s difficult to walk the line between genres, especially involving one that is meant to be factual, I think exploring past experiences and memories, even through the lens of other things like photographs and retellings, may be an important exercise in exploring our identities, our family histories, and even pushing the limits of what a genre can do. This collection is also such a unique examination of the human condition and its frailties… I’d hate to think that this is the last we could ever see of that conversation.

If it isn’t already shockingly clear, I was floored by this collection and fully intend to revisit it in the future. As a mother, I felt myself reeling with emotions, from hurt to anger to fury to protectiveness to love and back again, the ache to pick up and comfort a child, the rush of wondering why another mother figure wouldn’t… but even without children, I know this would have resonated deeply with a younger version of myself, a younger version who knew what conditional love and conditional contact was, who understood that love had to be earned (and maybe not even then). This collection truly has something in it for anyone who’s experienced empty, lacking connections, and who longed for love, for however long. Even if it’s written from the perspective of a young baby, its truth is ageless.

Order Your Copy of Puddin’ Here

Order Your Copy of Puddin’ Here

Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby: A Memoir in Prose Poems

Written by Patrick T. Reardon

Foreword Written by Haki R. Madhubuti

Third World Press (March 7, 2023), 130 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0883784259

$19.95

“Thank goodness someone was clever and creative enough to write imaginatively about the things that shape us during that brief spongelike period of life called babyhood. Everything, almost, is new and strange and makes us what we’ll spend the rest of our lives being. Brilliantly sensitive work.”—Vincent J. Schodolski

“Reardon’s Puddin’ is a work of inspiration, feeling, and craftsmanship that can be enjoyed in a single sitting but invites (and repays) careful re-reading. As a series of prose poems in the imagined words of a baby – not just any baby – Puddin’ has a language and imagery all of its own. There is also the keen insight, not only about infant intelligence and perception but also about the people and larger world that prompt wonder, delight, and puzzlement. As the author’s poignant Afterword suggests, the ripple effects may last a lifetime.”—Brian Spittle

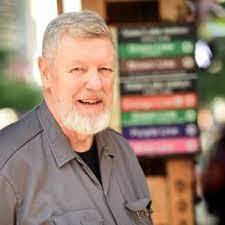

PATRICK T. REARDON is the author of fourteen books, including the poetry collections Requiem for David (Silver Birch Press), Darkness on the Face of the Deep (Kelsay Books), The Lost Tribes (Grey Book Press), Let the Baby Sleep (In Case of Emergency Press), and Salt of the Earth: Doubts and Faith (Kelsay Books). His memoir in prose poems Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby was published by Third World Press with an introduction by Haki Madhubuti. For 32 years, Reardon was a Chicago Tribune reporter. His history book, The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago was published by Southern Illinois University Press.

PATRICK T. REARDON is the author of fourteen books, including the poetry collections Requiem for David (Silver Birch Press), Darkness on the Face of the Deep (Kelsay Books), The Lost Tribes (Grey Book Press), Let the Baby Sleep (In Case of Emergency Press), and Salt of the Earth: Doubts and Faith (Kelsay Books). His memoir in prose poems Puddin’: The Autobiography of a Baby was published by Third World Press with an introduction by Haki Madhubuti. For 32 years, Reardon was a Chicago Tribune reporter. His history book, The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago was published by Southern Illinois University Press.

0 Comments